Seminars punish passive notes. You can “finish the reading,” highlight half the page, and still freeze when the professor asks, “So… what do you think?” If you want the best method for taking notes on seminars and readings, this guide is designed for you—mainly if your week includes labs, commuting, midterms, or a part-time job.

- Quick Start box: If you only have 10 minutes, do this…

- What Question-Led Notes are (and aren’t)

- From Notes to Talking Points

- How to do Q-LENS (step-by-step, with student examples)

- Question stems you can reuse

- Fast plans for behind, cramming, overwhelmed

- Mini Self-Check: Are Your Notes Seminar-Ready?

- Why this works (learning science, plain English)

- When this won’t work (edge cases)

- Troubleshooting (quick fixes)

- Common Student Mistakes (and the fix)

- Templates/Examples

- Comparison table

- Key Takeaways

- FAQ

- Conclusion

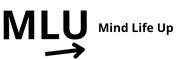

Snippet-ready definition: Question-Led Notes are notes organized around the questions you need to answer in discussion—so your notes become speaking points, not a transcript.

This method works for humanities seminars, social science readings, and even STEM-heavy courses when the goal is reasoning rather than memorization.

For the whole system (lectures + readings + revision), start here: [a simple note-taking system for any major].”

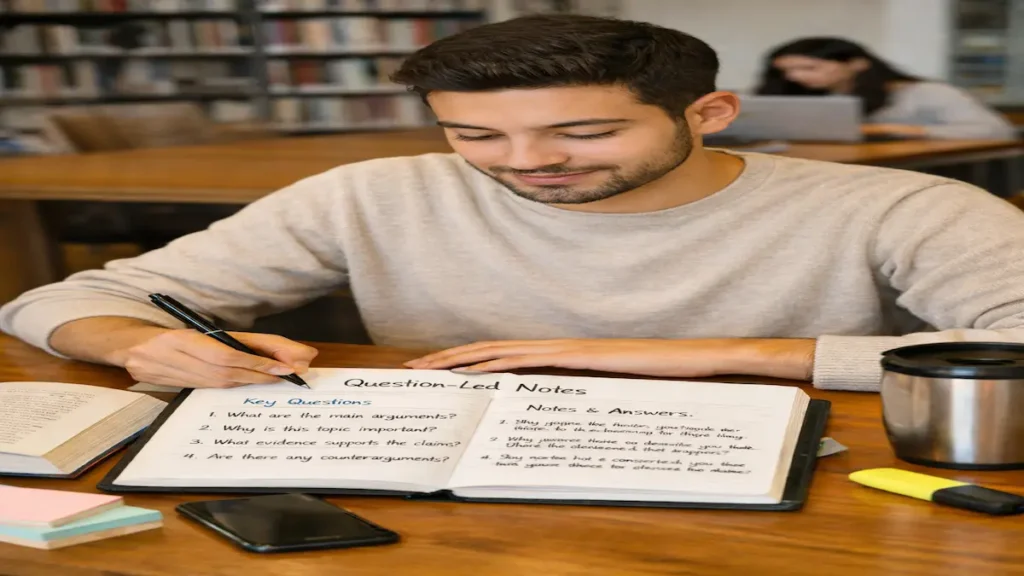

Quick Start box: If you only have 10 minutes, do this…

Open your reading and write three discussion questions at the top of the page.

Skim headings/abstract/intro for 2 minutes and guess the author’s central claim.

Pull two quotes or data points that support (or contradict) that claim.

Write 1 “So what?” line: why the claim matters for the course theme.

Bring those three questions + 3 lines to class. That’s enough to participate.

What Question-Led Notes are (and aren’t)

Question-Led Notes are not “everything the author said.” They’re not color-coded diaries.

They’re a tool for two outcomes:

You want to (1) understand the argument and (2) speak with confidence in a seminar.

Your notes should answer: What’s the claim? What’s the evidence? What do I say against myself when someone pushes back?

From Notes to Talking Points

If your notes don’t produce sentences you can say out loud, they’re not seminar notes.

Seminar success is basically three moves:

You summarize. You question. You connect.

Question-Led Notes force those moves while you read, not after you panic in class.

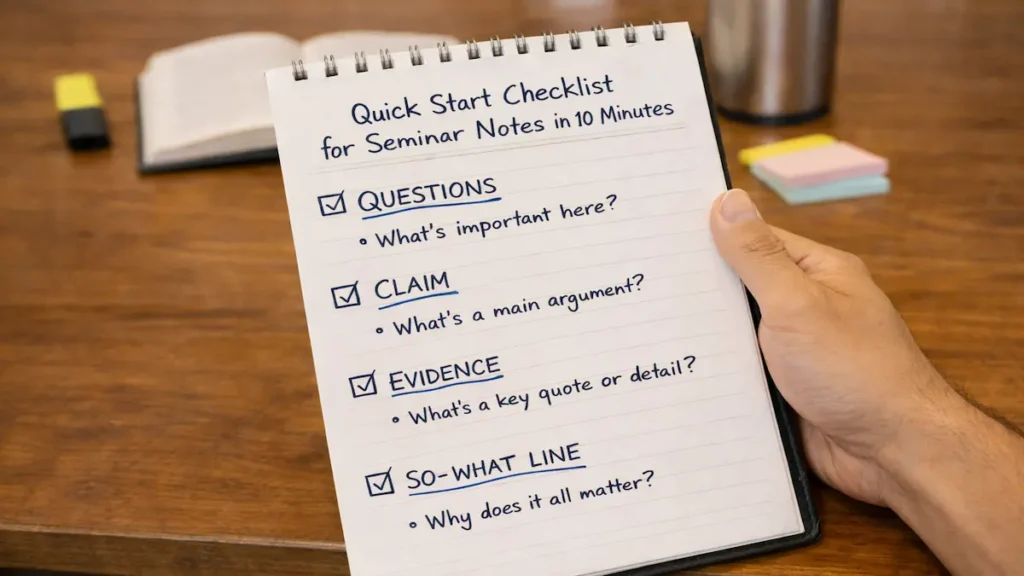

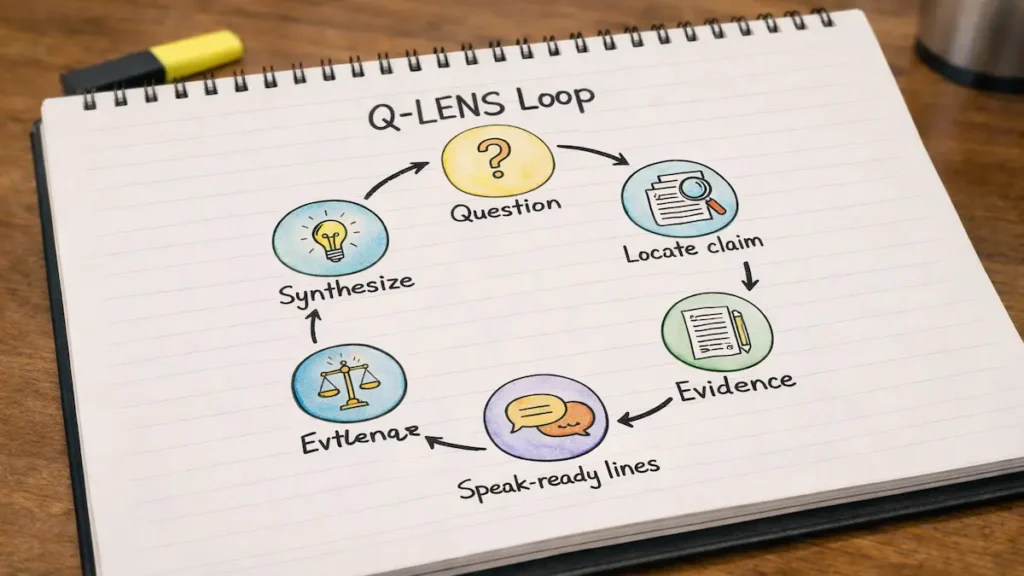

The Q-LENS Loop (6 steps)

Here’s the repeatable system you’ll use every time. Please keep it simple and consistent.

- Q — Question first (write the discussion prompt you wish you’ll get)

- L — Locate the claim (one sentence: what the author argues)

- E — Evidence grab (2–3 pieces: quote, example, data, method)

- N — Nuance & pushback (limits, assumptions, counterargument)

- S — Synthesize & connect (link to lecture/theme/another reading)

- Loop — Speak-ready lines (2 lines you can say in a seminar)

Now let’s turn that into notes you can actually use.

How to do Q-LENS (step-by-step, with student examples)

Step 1: Q — Question first

What to do: Before reading, write 2–3 questions at the top of your page. If you have a prompt, turn it into sub-questions. If you don’t, create your own.

Why it helps: Your brain reads differently when it’s hunting answers. You’ll notice structure, not just sentences.

Student example: On the bus to campus, you jot: “What is the author blaming?” “What’s their solution?” “What would a critic say?”

Step 2: L — Locate the claim

What to do: After the intro (or abstract), write one sentence: “The author argues that ___ because ___.”

Why it helps: Seminars revolve around claims. If you can’t state it cleanly, you can’t discuss it.

Student example: In a political theory seminar, you write: “They argue institutions shape ‘choice’ more than individual preferences.”

Step 3: E — Evidence grab

What to do: Capture 2–3 evidence pieces only if they support, complicate, or undermine the claim. Label each as Support / Complicate / Undermine.

Why it helps: Evidence is what lets you speak confidently, without having to reread.

Student example: In a psych reading, you note one key study design detail, one result, and one limitation mentioned by the author.

Step 4: N — Nuance & pushback

What to do: Add one “Yes, but…” line. Note assumptions, missing populations, alternative explanations, or where the argument might break.

Why it helps: Professors love nuance. This is how you move from “I read it” to “I can analyze it.”

Student example: During midterm season, you write: “Yes, but the sample is all first-years—does this generalize to commuter students?”

Step 5: S — Synthesize & connect

What to do: Write one connection to the lecture, lab, or another reading. Use: “This connects to ___ because ___.”

Why it helps: Seminar grades often reward integration over the course of the week. This makes connections automatic.

Student example: After a lab meeting, you connect a method’s reading to what your TA emphasized about controls.

Step 6: Loop — Speak-ready lines

What to do: Write two lines you could say out loud. One should be a summary; one should be a question or a challenge.

Why it helps: It turns notes into verbal output, which is what the seminar demands.

Student example: Right before class, you glance and say: “Their core claim is ___. My question is whether ___.”

Question stems you can reuse

Copy these into the top margin of your notes and pick the best fits for the reading:

- What problem is the author trying to solve—and why now?

- What’s the most substantial claim in one sentence?

- What evidence would change the author’s mind?

- What assumption is doing the most work here?

- Where would this argument fail in the real world?

- How does this connect to last week’s lecture theme?

- If I disagreed, what would my best counterargument be?

Fast plans for behind, cramming, overwhelmed

If you’re behind, the goal is not “perfect notes.” The goal is to survive the seminar and maintain learning momentum.

The “30-minute rescue” (for the night before)

Spend 10 minutes skimming the intro, headings, conclusion, and any bolded terms.

Spend 10 minutes doing Q-L-E (questions, claim, evidence).

Spend 10 minutes writing N + S + two speak-ready lines.

Walk into the seminar with: one claim, two evidence points, one pushback, one connection. You’ll be able to contribute even if you didn’t read every word.

The “90-minute catch-up” (for a rough week with work/lab)

First 30 minutes: read actively until you can write the claim without looking.

Next 30 minutes: evidence + nuance (aim for quality, not quantity).

Last 30 minutes: synthesize across readings—write one connection per reading to the course theme.

The “commuter mode” (10 minutes on transit + 10 minutes after)

On transit: write questions + guess the claim from the abstract/intro.

After: grab evidence + one “Yes, but…” line. That’s enough to talk.

Mini Self-Check: Are Your Notes Seminar-Ready?

Score yourself 1 point for each “yes.” Total it up.

0–2: Your notes are passive. Do Q + L + Loop next time.

3–4: You’ll participate, but your analysis may feel thin. Add Nuance.

5–6: You’re seminar-ready. Now focus on clarity and confidence.

| Check | Yes/No | Points |

|---|---|---|

| I wrote 2–3 questions before (or at the start of) reading | 1 | |

| I can state the author’s claim in one clean sentence | 1 | |

| I saved 2–3 evidence pieces labeled by purpose | 1 | |

| I wrote one pushback/limitation (“Yes, but…”) | 1 | |

| I made one connection to lecture/another reading/lab | 1 | |

| I have two lines I can say out loud in seminar | 1 |

Why this works (learning science, plain English)

Learning sticks when you actively retrieve and organize ideas, not when you reread or highlight.

Q-LENS forces three high-payoff behaviors:

It also reduces overload. Instead of tracking every detail, you track what matters for discussion: argument, Evidence, limits, connections.

When this won’t work (edge cases)

This approach can struggle when the assignment involves pure memorization (such as anatomy labeling) or when the professor tests minute details rather than arguments.

If your course is detail-heavy, use Q-LENS for conceptual understanding, then add a separate quick sheet for terms, formulas, or definitions you must recall verbatim.

Troubleshooting (quick fixes)

Problem: You can’t find the claim. Read the intro + conclusion only and write the best one-sentence claim you can. Refine later.

Problem: Your notes are too long. Cap evidence at three items. If it doesn’t support/complicate/undermine the claim, it doesn’t make the page.

Problem: You go blank in the seminar anyway. Before class, read only your two speak-ready lines out loud—twice. Your mouth learns faster than your eyes.

Common Student Mistakes (and the fix)

Mistake 1: Copying quotes with no purpose.

Fix: Label each quote Support / Complicate / Undermine. If you can’t label it, delete it.

Mistake 2: Writing “summary only” notes.

Fix: Add one pushback line every time. Even a simple “This assumes ___” is enough.

Mistake 3: Treating seminars like lectures.

Fix: Convert notes into lines you can say. If you can’t speak it, it’s not finished.

Mistake 4: Waiting until the last minute to connect readings.

Fix: Write one connection while you read. It saves you during midterms and papers.

Mistake 5: Trying to do this perfectly for every page.

Fix: Do Q-L-E-N-S once per section, not per paragraph. Consistency beats intensity.

Templates/Examples

Template 1: The one-page Q-LENS seminar sheet

Use this layout for each reading (paper, chapter, article):

Questions (2–3):

Q1:

Q2:

Q3:

Claim (1 sentence):

The author argues that ___ because ___.

Evidence (2–3, labeled):

- Support: ___

- Complicate: ___

- Undermine: ___

Nuance/pushback (1 line):

Yes, but ___.

Synthesis/connection (1 line):

This connects to ___ because ___.

Speak-ready lines (2 lines):

Line 1 (summary): ___

Line 2 (question/challenge): ___

Template 2: Seminar participation “scripts” (say these verbatim)

Summary opener: “The author’s main claim is ___, and they support it by ___.”

Question move: “I’m wondering whether ___, because ___.”

Connection move: “This reminds me of ___ from lecture/last week, since both ___.”

Pushback move: “A limitation might be ___, which could change the conclusion if ___.”

Template 3: Group project reading handoff (when you’re busy)

If you’re juggling a part-time job or lab hours, send your group this mini-brief:

Claim (1 sentence) + Evidence (2 bullets in a message, not a list in your notes) + One pushback + One discussion question.

That’s enough to contribute without doing a complete rewrite.

Comparison table

| Method | What it’s best for | Where it fails in seminars | Best use case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Question-Led Notes | Discussion, analysis, connecting readings | Not ideal for pure memorization | Seminars, reading-heavy classes, paper prep |

| Cornell Notes | Capturing lecture structure | Often turns into summary without debate | Lecture-based courses with clear key points |

| Highlighting + rereading | Quick exposure | Feels familiar but doesn’t create speaking points | Only as a first skim, not a final study method |

| Outline notes | Organizing long chapters | Can miss argument + pushback | When you must track structure, then add Q-LENS lines |

Key Takeaways

Takeaway 1: Start with questions to give your reading purpose.

Takeaway 2: One clean claim beats a page of copied sentences.

Takeaway 3: Save only evidence that changes your understanding.

Takeaway 4: Add one “Yes, but…” line to sound analytical fast.

Takeaway 5: Write two speak-ready lines so you can participate on low sleep.

Takeaway 6: If you’re behind, do the 30-minute rescue and show up anyway.

FAQ

How many questions should I write before a seminar reading?

Aim for 2–3. More than that can scatter your focus, especially if you’re reading between shifts or classes.

What if the reading is confusing and I don’t “get it”?

Write your best guess at the claim, then write one honest question about what you don’t understand. That question is often a substantial contribution to the seminar.

Can I use this for labs or STEM courses?

Yes for conceptual readings (methods, ethics, theory, research design). For problem sets, pair it with a separate formula/steps sheet.

How can I utilize these notes to prepare for the midterms?

Use the claim + pushback lines as prompts. Cover the page and try to explain the argument out loud in 60 seconds, then check what you missed.

I talk too little in the seminar—will this actually help?

It helps because you walk in with sentences already formed. If you’re anxious, use one script line early, then ask one question midway through the discussion.

Conclusion

If you want the best way to take notes in seminars, stop writing notes that stay trapped on paper. Write notes that turn into sentences you can actually say out loud. Question-based notes do that—fast, repeatable, even during weeks packed with commuting, labs, and a part-time job. Try Q-LENS in your next reading, and you’ll feel the difference as soon as the discussion starts.