If you’ve ever looked down mid-class and realized you’ve been typing everything—yet you still don’t understand it—you’re not alone. note taking during lectures works best when it’s selective: you capture the structure and meaning, not every sentence.

- Quick Start box: If you only have 10 minutes, do this…

- The One Rule That Decides What to Write vs What to Skip

- note taking during lectures: fast cues that tell you “write this”

- The FAST Cues System (a simple, repeatable workflow)

- Example Box: What “write vs skip” looks like in a real lecture

- Three realistic examples (lecture + lab + real life)

- If you’re behind or overwhelmed: what to do today + the next 48 hours

- Mini diagnostic: Are your notes helping you learn (or just keeping you busy)?

- How to turn notes into exam-ready study (without rewriting everything)

- Common Student Mistakes (and the fix)

- Templates/Examples (checklist/study plan/scripts/rubric)

- Brief comparison table

- Key Takeaways

- FAQ

- Conclusion

Definition (snippet-ready): Effective lecture notes are a condensed record of the professor’s key ideas, how they connect, and what you should be able to explain later—without copying the whole talk.

This is for college students dealing with fast slides, accents, big survey classes, labs, and real-life constraints (commuting, back-to-back lectures, or a part-time shift right after class).

Quick Start box: If you only have 10 minutes, do this…

- Open a fresh page and write today’s topic + date at the top.

- Make three sections: Big Idea, How it Works, Exam Triggers.

- As the professor talks, write only definitions, steps, examples, and “why this matters.”

- When you get lost, drop a [?] marker and keep listening—don’t freeze.

- After class, add a 3–5 line “teach-back” summary from memory (then check the lecture slides).

The One Rule That Decides What to Write vs What to Skip

Here’s the filter that keeps you fast: Write what you’d need to answer a question later. Skip what you could reread in the textbook or slides without losing meaning.

Next step: Put a tiny “Q” in the margin whenever something sounds testable. That one habit makes your notes aim at exam revision instead of transcription.

What to write (high-value)

Capture information that changes how you think about the topic or how you’d solve a problem:

- Definitions in the professor’s words (especially if they simplify the book’s version)

- Relationships (cause/effect, compare/contrast, “this leads to that”)

- Processes and steps (what happens first, next, and why)

- Worked examples (what they chose, what they ignored, and the turning point)

- Flags like “common mistake,” “you’ll see this again,” “this is important,” or “in the real world…”

Next step: When you hear a flag phrase, write one clean line labeled “Why it matters:” and finish the sentence.

What to skip (low-value)

Skip anything that doesn’t add meaning or can be recovered later:

- Long stories that don’t connect back to the concept

- Repeated phrasing (“as I said earlier…”)

- Full sentences from the lecture slides (unless the slide is missing context)

- Administrative chatter (unless it changes your grade or deadlines)

Next step: If you notice you’re copying full sentences, force yourself to rewrite the idea in 7–12 words instead.

note taking during lectures: fast cues that tell you “write this”

Fast lectures feel impossible until you start listening for cues. Professors signal what matters—your job is to catch the signals.

Next step: Choose two cues from the list below and focus on them in your next class. Don’t try to master all at once.

The best cues (in plain English):

When the professor…

- Defines a term (“X is…”)

- Contrasts two things (“Unlike A, B…”)

- Lists steps (“First… second…”)

- Explains a mistake (“People often confuse…”)

- Adds context beyond slides (“The slide says X, but what it really means is…”)

- Predicts an exam angle (“You should be able to…”)

A good mental trick: if you can imagine it becoming a short-answer prompt, it belongs in your notes.

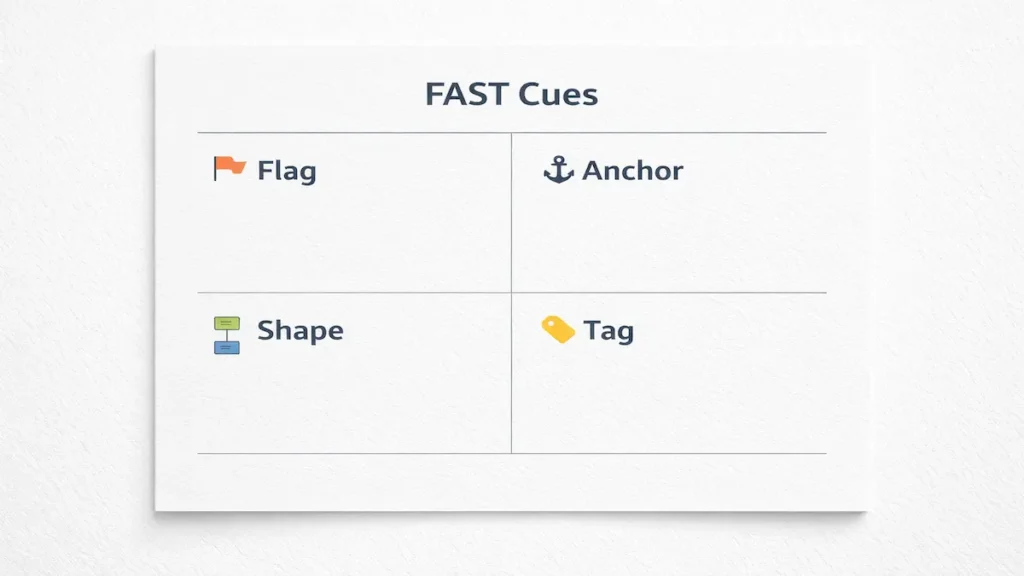

The FAST Cues System (a simple, repeatable workflow)

This is the system you can use in any course—psych, econ, bio, engineering—without changing your whole life.

FAST = Flag, Anchor, Shape, Tag

Flag: Mark moments that sound testable (star, “Q,” or underline).

Anchor: Write the simplest version of the idea (one line).

Shape: Add the structure (steps, comparison, or cause/effect).

Tag: Add a quick label so you can study later (“definition,” “example,” “common error,” “formula use”).

Next step: Write “FAST” at the top of your next page. When you drift into copying, look up and return to the four moves.

Before class (2 minutes)

Do a tiny setup that makes speed possible:

- Write the topic and pull up the lecture slides (if posted).

- Leave wide margins for tags and questions.

- If you’re in a lab-heavy course, reserve a mini area labeled Lab notebook link to connect lecture concepts to procedures.

Next step: If slides exist, skim just the headings so you already know the “shape” of the lecture.

During class (how to keep up without panic)

Your job isn’t to capture everything—it’s to track the spine of the lecture.

- When the professor is explaining, prioritize Anchor + Shape.

- When they’re giving an example, capture the turning point (what changed the answer).

- When you miss something, drop [?] and keep listening.

This is where learning science suggests retrieval practice matters: staying mentally present beats perfect notes you never reread.

Next step: The moment you place a [?], also write the nearest keyword so you can ask in office hours or check later.

After class (10 minutes that pays off)

This is where notes turn into memory:

- Write a short teach-back: “Today was about ___, which works because ___.”

- Add one active recall question you could quiz yourself on later.

- If you commute, do this on the bus with headphones—no heavy studying, just cleanup.

Next step: Set a 10-minute timer. Stop when it rings. Consistency beats marathon sessions.

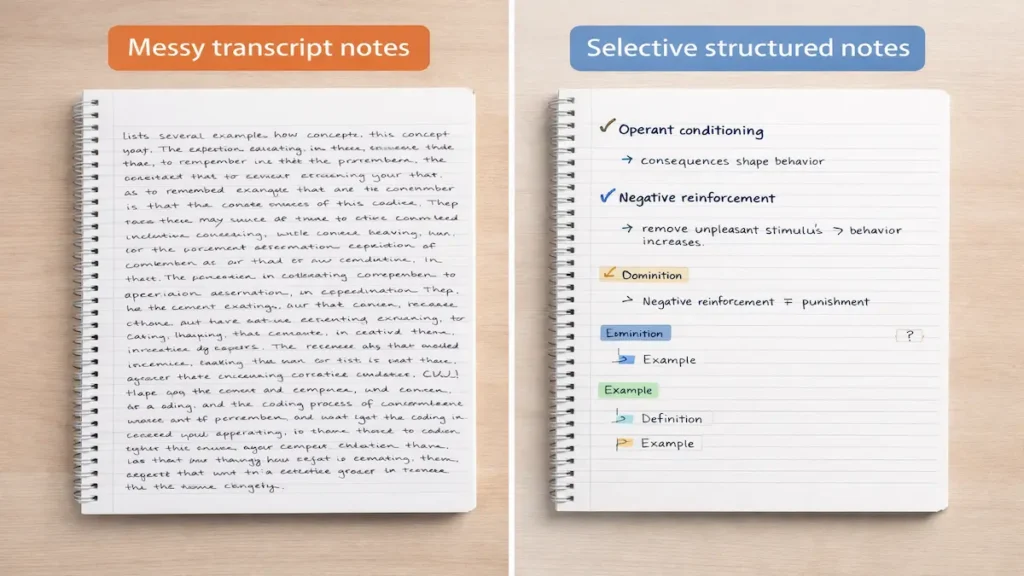

Example Box: What “write vs skip” looks like in a real lecture

Course: Intro to Psych

Professor says: “Operant conditioning is about consequences shaping behavior… Negative reinforcement isn’t punishment—it removes something unpleasant to increase behavior.”

Write:

- Operant conditioning = behavior shaped by consequences

- Negative reinforcement: remove unpleasant stimulus → behavior increases

- Common confusion: negative reinforcement ≠ punishment

- Skip: A long anecdote about a neighbor’s dog (unless it clarifies the confusion)

Next step: In your next lecture, try capturing one “common confusion” line. Those are exam magnets.

Three realistic examples (lecture + lab + real life)

Example 1: Big lecture with dense slides

If the slides are packed, don’t copy them. Write what the slides don’t give you:

- Why the concept matters

- How to choose between two similar ideas

- What the professor emphasizes verbally

Next step: If you must copy anything, copy only the slide’s diagram labels plus the professor’s explanation of what moves first.

Example 2: Lab course where procedures matter

In labs, the trap is writing every instruction word-for-word. Instead, connect purpose to steps:

- What is the goal (what are we measuring?)

- The critical steps where errors happen

- How results should look if done correctly

Link the lecture concept to your lab notebook so the theory and procedure stay connected.

Next step: After lab, write one line: “If my results look weird, the first thing to check is ___.”

Example 3: Midterms week + part-time job + back-to-back classes

When you’re exhausted, your brain wants to type everything to feel safe. That backfires. Use tags:

- “Exam trigger” when the professor hints at the test format

- “Need later” when it connects to upcoming problem sets

- “[?]” when you can’t keep up

Then, later that night, do spaced repetition with a few flashcards—not your whole notebook.

Next step: Pick five tagged lines and convert them into questions. That’s your minimum effective study.

If you’re behind or overwhelmed: what to do today + the next 48 hours

You don’t need to “catch up” by rewriting everything. You need a triage plan.

Today (30–60 minutes)

- Grab the slides from the last lecture and your messy notes.

- Write a summary from memory first (even if it’s rough).

- Fill gaps using slides, then your textbook, then a classmate as a last resort.

Next step: Email or message one specific question (not “what did I miss?”). Example: “Can you confirm the difference between X and Y from Tuesday?”

Next 48 hours (two short sessions)

Session 1: Build a one-page concept map from your summaries (big ideas and links).

Session 2: Do retrieval practice: quiz yourself on the tags and the “common confusion” lines.

If you can, visit office hours with your [?] markers. Professors answer faster when you show your attempt.

Next step: Put two 25-minute blocks on your calendar—one tomorrow, one the day after. Protect them like a class.

Mini diagnostic: Are your notes helping you learn (or just keeping you busy)?

Score yourself quickly. Give 1 point for each “Yes.”

| Check | Yes/No |

|---|---|

| I can explain the main idea without looking at my notes. | |

| My page shows structure (steps, contrasts, cause/effect), not just sentences. | |

| I have at least one “common mistake/confusion” captured. | |

| I marked questions ([?]) instead of stopping when lost. | |

| I did a 10-minute cleanup at least once this week within 24 hours. | |

| My notes include at least one worked example or decision point. |

Scoring:

5–6 = strong system (keep it consistent).

3–4 = you’re close (tighten your cue focus).

0–2 = you’re transcribing (switch to FAST and do the 10-minute cleanup).

Next step: If you scored 0–2, choose one class this week to practice, not all of them at once.

How to turn notes into exam-ready study (without rewriting everything)

Good notes are a launchpad. The learning happens when you test yourself.

Use this flow:

- Turn headings into questions.

- Answer from memory (even partially).

- Check your notes and correct.

- Repeat later using spaced repetition.

This is where active recall beats rereading, especially for cumulative finals.

Next step: Tonight, choose one page of notes and create three self-quiz questions from it. Keep it small.

Common Student Mistakes (and the fix)

Mistake 1: Copying the lecture slides word-for-word

Fix: Only write what the professor adds beyond the slide: meaning, exceptions, and examples.

Mistake 2: Freezing when you miss one line

Fix: Drop [?] and keep listening. Fill gaps later.

Mistake 3: Notes with no structure

Fix: Force a shape: steps, comparison, or cause/effect. One of these always fits.

Mistake 4: “Pretty notes” that take forever

Fix: Ugly during class, clean after. The 10-minute cleanup is the win.

Mistake 5: Never using notes again

Fix: Convert tags into questions and practice retrieval. Notes are not the end product.

Templates/Examples (checklist/study plan/scripts/rubric)

1) FAST page template (copy/paste)

Topic/Date:

Big Idea (1–2 lines):

Anchor lines (simple statements):

Shape (steps / compare / cause-effect):

Tagged lines:

- (definition) ...

- (example) ...

- (common error) ...

[?] Questions to ask / look up:

Teach-back (3–5 lines after class):

3) Office hours script (30 seconds)

Hi Professor ___. I’m reviewing my notes from (date/topic).

I’m stuck on: (specific concept).

Here’s what I think it means: (your 1–2 line attempt).

Can you confirm the difference between ___ and ___ / the step I’m missing?

4) Two-day catch-up plan (when midterms hit)

Day 1: Summaries first → fill gaps from slides → mark 5 exam triggers

Day 2: Self-quiz → correct → make 10 flashcards max → quick review

Brief comparison table

| Method | Best for | Risk | Quick tweak |

|---|---|---|---|

| Outline style | Fast talkers, concept-heavy courses | Can become a transcript | Add tags: definition/example/error |

| Cornell-style columns | Review and self-quizzing | Takes setup time | Use it only for tough lectures |

| Diagram/flow layout | Processes (bio, chem, CS) | Messy if you overdraw | Keep diagrams minimal; label arrows |

| “FAST” cues workflow | Any class, especially fast lectures | Requires discipline to skip | Use [ ? ] markers to avoid freezing |

Key Takeaways

- Selective notes beat perfect transcripts because they preserve meaning and structure.

- Listen for cues: definitions, contrasts, steps, mistakes, and “you should be able to…” signals.

- Use FAST (Flag, Anchor, Shape, Tag) to stay organized without slowing down.

- When you miss something, mark it and keep listening—fix gaps later.

- A 10-minute cleanup within 24 hours makes your notes study-ready.

- Turn your notes into questions for retrieval practice and spaced repetition.

FAQ

How do I take notes if the professor talks too fast?

Stop trying to write full sentences. Capture anchor lines and the lecture’s structure, then mark gaps with [?] to fix after class.

Should I type or handwrite?

Either can work. Typing is faster for dense classes; handwriting can help you stay selective. The real key is your filter (what you choose to capture).

What if I don’t have the lecture slides?

Lean harder on structure: definitions, steps, and examples. After class, ask a classmate for one missing piece, not their entire notes.

How soon should I review after class?

Same day is ideal, but even a 10-minute cleanup within 24 hours helps. That short window prevents small gaps from becoming a full catch-up crisis.

How do I handle labs differently?

Focus on purpose, critical steps, and common errors. Link the concept to your lab notebook so you can explain why the procedure works.

Conclusion

Once you stop treating class like a recording session and start treating it like a decision-making process, everything gets easier. With the FAST cues, a simple write/skip filter, and a short post-class cleanup, note taking during lectures becomes a tool for understanding—not just a pile of pages.